A full harvest of corn destroyed by uncharacteristic snow

Have you heard of the U.S. and European disaster that took place in 1816 all because of a volcano that erupted halfway across the world? It’s definitely worth taking note of.

In 1816, an extraordinary event unfolded: summer never came. Frost in July, snow in August, and crop failures across the Northern Hemisphere led to what became known as the “Year Without a Summer.” This climate catastrophe, triggered by the massive eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia the previous year, serves as a stark reminder of how events on one side of the globe can have devastating consequences worldwide.

The eruption of Mount Tambora, over 7,000 miles away from North America and Europe, ejected massive amounts of volcanic ash and sulfur dioxide into the atmosphere. This created a veil that blocked sunlight and dramatically cooled the Earth’s surface. The result was a year of extreme weather that no one saw coming, highlighting the interconnectedness of our global climate system and the far-reaching impacts of natural disasters.

For people in 1816, the consequences were dire. Imagine waking up to frost on your crops in the middle of July or having to shovel snow in August. The year became grimly known as “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death.” Crop failures were widespread and devastating. Corn, which typically required a long, warm growing season, failed to mature in many areas. Wheat, oats, and potatoes suffered similarly. In parts of New England, less than half the hay crop survived, leading to mass slaughters of livestock that couldn’t be fed through the winter.

The food scarcity that ensued was severe. With crops failing across vast regions, many communities faced starvation. Food prices skyrocketed, putting

Due to fuel shortages, people had to burn their furniture in order to stay warm

even basic sustenance out of reach for many. In parts of Europe, the price of grain increased by 800%. Foraging became a survival skill, with people resorting to eating nettles, hedgehogs, and even cats and rats. Famine and malnutrition led to increased susceptibility to disease, compounding the crisis.

Surprisingly, fuel shortages also became a critical issue, due to the cold temperatures. The prolonged winter weather increased the demand for firewood, quickly depleting easily accessible supplies. Wet conditions made it difficult to harvest and dry wood, exacerbating the shortage. In some areas, people resorted to burning furniture or parts of their homes to stay warm. The scarcity of fuel meant that even those with access to food often couldn’t cook it properly, further contributing to nutritional deficiencies.

The Year Without a Summer offers crucial insights for modern preparedness. It underscores the importance of diversifying food sources – those who survived best in 1816 had multiple ways to obtain food. Today, this might mean growing your own food, supporting local farmers, and storing a variety of long-term food supplies. The crisis also highlights the value of adaptability. Farmers who quickly switched to cold-resistant crops fared better, reminding us to be ready to pivot our plans and learn versatile skills.

Community resilience proved vital during this time. Areas where people banded together had higher survival rates, emphasizing the importance of building local networks and participating in community preparedness initiatives. Those with food reserves weathered the crisis better, underscoring the value of building a deep pantry and learning food preservation techniques.

The fuel shortages of 1816 remind us of the importance of energy independence. In our modern context, this might mean considering alternative energy sources like solar or wind power, having non-electric heating methods on hand, and implementing energy-efficient home modifications.

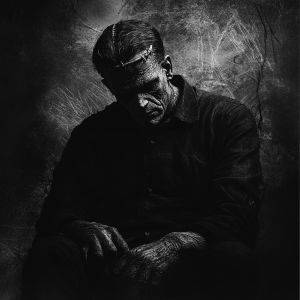

Frankenstein was inspired during the dreariness of the 1816 Summer That Never Was

An interesting fact, not preparedness related…The Year Without a Summer left its mark not just on agriculture and economy, but on culture as well. In Switzerland, a group of writers, forced to stay indoors due to the dreariness outside, engaged in a now-famous writing contest. Among them was Mary Shelley, who began writing what would become her iconic novel “Frankenstein.” The gloomy, chilling atmosphere of that sunless summer is reflected in the dark, Gothic tone of her masterpiece. Similarly, Lord Byron wrote his poem “Darkness” during this time, directly inspired by the unnatural gloom. This eerie summer thus inadvertently contributed to some of the most enduring works of Gothic literature, demonstrating how climate events can influence art and culture in profound and lasting ways.

The Year Without a Summer serves as a sobering reminder of nature’s power and the global interconnectedness of our world. While we can’t predict every disaster, we can learn from history to build resilience. By diversifying our resources, adapting quickly, strengthening our communities, and planning for long-term sustainability, we can better face whatever challenges the future may bring. In an age of climate change and global uncertainties, the lessons of 1816 are more relevant than ever.