The Australian Aboriginal people have a deep connection with their land, having developed survival techniques that would make Bear Grylls green with envy. One of their most ingenious methods is finding water stored in tree roots. Now, before you start digging up every tree in sight like a caffeine-addled squirrel, let’s break down this technique.

First off, not all trees are created equal when it comes to being nature’s water coolers. The Aborigines primarily look for two types of trees: the Desert Oak (Allocasuarina decaisneana) and the River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis). These trees are the camels of the plant world, storing water in their roots for those “just in case” moments. And in the Australian outback, it’s always a “just in case” moment.

The Desert Oak, with its scraggly appearance, might not win any beauty pageants, but it’s a superstar in water storage. Young Desert Oaks, affectionately known as “pencil pines” due to their slender shape, are particularly good at this hydration hoarding. They spend their early years developing a massive taproot that can plunge up to 10 meters deep into the ground. This taproot acts like a giant straw, sucking up any available moisture and storing it for later use. It’s like the tree equivalent of that friend who always orders extra fries “just in case.”

The River Red Gum, on the other hand, is the overachiever of the Eucalyptus world. This tree doesn’t just store water; it’s practically a natural GPS for finding it. River Red Gums tend to grow where their roots can access underground water, making them excellent indicators of subterranean water sources. If you see a River Red Gum, there’s a good chance you’re standing above a hidden water source. It’s nature’s way of saying, “Dig here, you thirsty fool!”

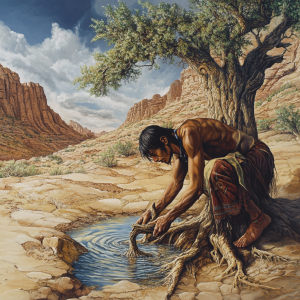

Now, onto the fun part – actually getting the water. The Aboriginal technique involves selecting a likely tree and then digging to expose its roots. They look for roots about the thickness of your arm – anything smaller might not be worth the effort, and anything larger might require you to dig halfway to China. Once a suitable root is found, it’s extracted and cut into sections about 30-40 cm long.

Here’s where it gets interesting. These root sections are then propped vertically against each other or a support, with one end slightly raised. As if by

Aboriginal people harvest water from particular tree roots

magic (but really by gravity and plant biology), water begins to drain from the lower end. It’s like squeezing a sponge, except the sponge is a tree root, and you’re not actually squeezing it. The water collected is usually clear and perfectly drinkable, although it might have a slightly woody taste. Think of it as nature’s artisanal water – hipster cafes would probably charge a fortune for this stuff.

One important note: this technique requires some serious respect for nature. The Aborigines, with their deep connection to the land, understand the importance of not damaging the tree beyond repair. The Aboriginal people’s technique for extracting water from tree roots is not just clever; it’s also surprisingly gentle on the trees themselves. Guided by a deep respect for nature and thousands of years of traditional knowledge, they’ve perfected a sustainable harvesting method that ensures the trees live to quench another day’s thirst. When selecting a tree, they choose carefully, opting for roots about the thickness of a wrist while avoiding the larger, life-sustaining main roots. They’ll only take from one or two roots, leaving the rest of the tree’s underground network untouched. The extraction process is more like careful surgery than excavation, with only a section of the chosen root removed. After the life-saving water has been drained, the remaining root sections are often reburied, giving them a chance to regrow. To prevent overtaxing any single tree, they rotate their harvesting spots and typically perform this technique during cooler months when the trees are under less stress. This thoughtful approach, passed down through generations, showcases a remarkable balance between survival needs and environmental stewardship. It’s a poignant reminder that true survival skills are as much about preserving resources as they are about using them.

This water-finding technique is more than just a survival skill; it’s a testament to the incredible knowledge and understanding that Aboriginal people have developed over tens of thousands of years. It’s a reminder that sometimes, the most vital resources are hidden right beneath our feet, waiting for those with the knowledge and respect for nature to find them.

Juniper trees store water in their roots

While the water-storing abilities of Australian trees might seem like a unique adaptation to the harsh outback, it’s worth noting that we have some impressive hydro-hoarders right here in the United States. Trees like the cottonwood, mesquite, and juniper have developed their own water-storing superpowers to cope with varying levels of aridity. The mesquite, for instance, sends its roots on a deep-diving expedition, sometimes plunging over 150 feet into the earth in search of water. Cottonwoods, despite their preference for wetter areas, can store water in their extensive root systems, acting as natural reservoirs. And let’s not forget the hardy juniper, spreading its roots far and wide to slurp up whatever moisture it can find. While we might not be tapping these trees for emergency water anytime soon (and please don’t start digging up your local park), it’s a reminder that nature’s ingenuity isn’t limited to the Australian continent. These adaptations underscore the importance of understanding our local ecosystems in the broader context of preparedness and survival skills.

So, the next time you find yourself in the Australian outback (which, let’s face it, probably won’t be anytime soon unless you’re particularly unlucky or have a very strange bucket list), remember the humble tree root. It might just be your ticket to survival, provided you can remember which trees to look for and don’t mind a bit of digging. Just remember to bring a shovel – trying to dig with your bare hands will likely leave you more dehydrated than when you started. And maybe, just maybe, you’ll gain a new appreciation for both the ingenuity of the Aboriginal people and the secret life of trees. Who knew that these silent sentinels of the outback were also nature’s own water bottles?